The AI Octopus, Ambani's milkshake, '90s nostalgia, and perfect harmonies

August 21, 2020 Edition

Hi gang, and happy Friday from California, also known as Ground Zero for the Apocalypse. A pandemic and months of unrest weren’t enough for our fair state; now, we have the worst heat wave in 70 years, rolling blackouts, and a delightful phenomenon known as fire tornadoes. Other than that, it’s a good time.

Source: J.A.K., New Yorker, August 2020

AI extends its tentacles

Once upon a time, AI was found primarily in sci-fi novels (see William Gibson, for one) and specialist nonfiction domains. Over time, mainstream culture expanded to include these influences; countless films & TV shows incorporated elements of sci-fi writing, and popularized the notion of AI. In the past decade or so, this trend has deepened, with examples including TV shows like Westworld (2016-) & Black Mirror (2011-), and movies like Her (2013) & Ex Machina (2014). This collision between the pop cultural investigation of AI and the intellectual/technical exploration thereof has contributed to several years of endless existential handwringing about the singularity and artificial general intelligence, not to mention thought experiments like Roko’s Basilisk (@Reader BNH, cover your screens!).

In the business world, we’ve moved definitively into an “applied” or “functional” phase of our relationship with AI, in its many forms. Even distinctly non-magical applications--like ML-powered digital ad campaigns--generate remarkable real world results. We take these things for granted, often unaware of the complexity under the hood and the years of foundational intellectual property that had to be developed before we could get here.

Recently, it’s felt like we’re beginning to experience a new “pop app” stage of AI, for better and for much worse. I think of this as a moment when more mainstream consumers start to encounter and consume AI-based products and content: articles, videos, sounds, images, games, apps, and more. You probably won’t be surprised that this is a double-edged sword.

Part of what’s happening is that the media is becoming more knowledgeable about AI, and more interested in its tangible manifestations. AI research is now covered in mainline news outlets, and by writers who otherwise produce opinion or cultural commentary. There is an implicit appeal to readers: the science fiction that you saw in so many movies over the past several decades is now real, and often stranger and more powerful than envisioned. And, there is a persistent suggestion that readers should care about these trends because they will reshape the way we live and, especially, work: your livelihood is at stake, if these machines ever figure it out.

Beyond media coverage and general consumer awareness, there is also the fact that many AI-based tools and experiments are becoming better and more accessible to a broader cross-section of people. In weeks past, I’ve mentioned deepfake generators, voice modulators, and algorithmic music generation tools: none of those require anything more than an internet-connected device and some spare time and curiosity. These technologies are “out of the lab,” as it were, and increasingly moving into the application phase of development.

One need only look at the much-publicized June 2020 release of OpenAI’s GPT-3 to witness the convergence of these related trends. In shorthand, GPT-3 (which stands for “Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3”) is a language model produced by OpenAI (a research and deployment company co-founded by Elon Musk and YC’s Sam Altman, with a suitably grandiose mission statement) that uses deep learning to predict and produce text. [It occurs to me that a mission statement generator would be a life-changing use of this technology, and one that might save all of us many hours of existentially draining meetings on this topic.] GPT-3 was trained on “hundreds of billions of words,” and has 175bn machine learning parameters. Needless to say, it’s powerful, and captured the imagination of many through its ability to approximate a wide range of “human-like” text. In particular, the Tech Twitter World—also known as the Tenth Circle of Hell—has been ablaze (👏) for the past few weeks with discussions and homegrown experiments with the underlying technology. It isn’t always pretty, as you might expect from a predictive, generative text engine that was trained on text from the internet; as one investor said to me, “it starts out relatively okay, but pretty soon you’re talking to a Klansman.”

People have used GPT-3 to write articles, stories, poetry, and even code in certain (constrained) cases. A college student used it to compose a fake blog whose first post reached the #1 position on Hacker News (MIT Technology Review). Arram Sabeti, a developer/artist, showcased a number of other GPT-3 outputs, with notably good results (including a Raymond Chandler-style noir screenplay about Harry Potter). Sharif Shameem demonstrated how GPT-3 could be used to create a no-code layout generator (MIT Technology Review): simply write how you want something to appear on screen, and the rest takes care of itself. That MIT Technology Review article also includes numerous examples of the ugliness that GPT-3 mirrors back at us: sexism, racism, and all the other -isms you’d imagine. This is to say nothing of the potential for “weaponization” of mass disinformation that OpenAI and others have acknowledged as a possibility.

Ultimately, the word “mirror” is pretty appropriate. GPT-3 predicts what word “should” come next based on the data on which it has been trained. As Will Douglas Heaven writes, this makes it “shockingly mindless,” as there is no metacognition. I suppose that’s mildly comforting? As others have noted, GPT-3 is good at stringing words together but not with logic, new ideas, or conceptual coherence; that makes it eerily similar to your humble narrator.

This is just one example of AI’s pop phase, but there are numerous other manifestations across creative genres. In June, it was announced that, for the first time ever, an AI robot named Erica would play a leading role in a feature film (Hollywood Reporter). [I will restrain myself from comments regarding the difference between this “humanoid actor” and many of its actual Hollywood precursors.] Meanwhile, in the design world, a Russian design firm reportedly “passed off computer-generated work as human” (Fast Company), to the amusement (not anger) of its clients. Indeed, a glance at the logos produced by Nikolay Ironov reveals the genuine quality of his (its?) work:

Of course, it’s not hard to move from “cool AI creations” to “deepfake central.” To be fair, not all deepfakes are dangerous. Input’s Andrew Paul recently wrote a story about whether inserting a deepfake Harrison Ford into Solo: A Star Wars Story would have helped the film’s pedestrian box office results. Paul cites a particularly smooth deepfake face-swap created by YouTuber Shamook:

Weird, but sort of impressive, right? If you’re into that sort of thing, there’s an app called Reface that “uses AI-powered deepfake technology to let users try on another face/form” (Tech Crunch): the 2020 equivalent of walking a mile in someone else’s shoes? I can’t possibly imagine how this could go wrong. Perhaps a totally untraceable deepfake agent (Reuters) who conducts online harassment? This is all to say nothing of tools that enable audio deepfakes (ostensibly for wholesome production purposes) and voice modulating technologies, all of which are becoming more prevalent.

I’m far from an AI/deepfake expert, and I claim no technical knowledge of the underlying IP. What I find interesting is the question of AI-based tools in producing content, and what their usage means for how we think about authorship, ownership, quality, and remuneration. I’ve written about this in the past, and continue to wonder to what extent we would discount, say, “the great American novel” if we learned that it had been written partly (or entirely) using an AI-based model. What if the human writer herself had not only created the narrative, but also tuned the supporting AI?

I am reminded of my first experiences using Smart Reply and Smart Compose in Gmail: they were helpful and efficient, but they didn’t generate text that sounded “like me.” The output was passable, but felt like a mis-calibrated composite: too cheerful, or too formal; too brisk, or too casual. Technically correct but spiritually deficient, shall we say. Yet, as these technologies improve, we will almost certainly face more instances where we consume content that is produced more by a machine than by a human; with that will come a myriad of questions around who is responsible for the work, its underlying meaning and import, and—perhaps most pressingly for creators—to whom compensation should be directed.

Ambani drinks your lassi

It’s pretty cool to be Asia’s richest man, or so they tell me. Fresh off raising $20bn for Jio Platforms, Mukesh Ambani is apparently leading a “shopping spree” (Bloomberg) on behalf of his oil/retail/telco conglomerate parent, Reliance. The potential targets include Urban Ladder (an online furniture seller), Zivame (a lingerie maker), and NetMeds (medicine delivery), the last of which confirmed that Reliance had acquired a majority stake for $83M (Tech Crunch).

The strategy makes sense, as the pandemic has put tremendous pressure on retail businesses across the globe, thus depressing valuations for offline retail while accelerating the adoption of online commerce. Reliance is cash-rich and able to consolidate its position across a range of industries. Further, as complementary products like JioMart (now being integrated with Whatsapp) expand Reliance’s suite of commerce offerings, the company continues to pursue several investing theses: providing the internet and device infrastructure to bring Indians online, social and communications tools to connect them, vertical commerce and entertainment experiences to entice the burgeoning middle class, and horizontal fintech solutions to facilitate digital spending.

You can keep 2020, for all we care

One marginal silver lining to the unmitigated—and perhaps accelerating—disaster that constitutes 2020 is a wave of creatively channeled nostalgia. You know, for the good old days: the ‘90s! Ah yes, when all we had to worry about was the Soviet Union, or apartheid, or the LA riots, or imminent Y2K, or bloody civil/ethnic wars on multiple continents. Simpler times.

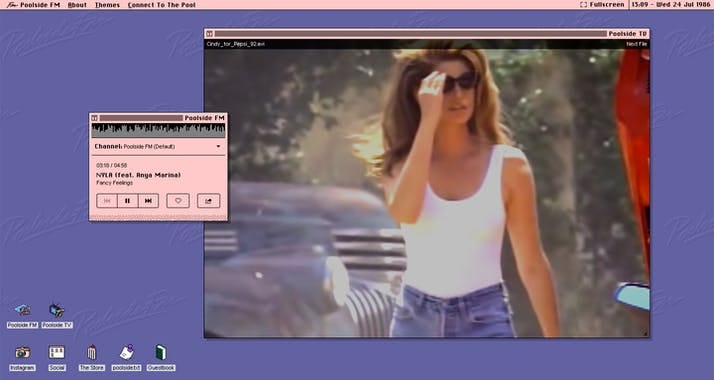

But, I digress. For whatever reason, in recent weeks, I’ve discovered multiple “throwback” products whose design aesthetics call back to the end of the 20th century. I will admit to strolling down memory lane rather pleasurably. First, since it is most incontrovertibly summertime, I present Poolside.fm. Best experienced on desktop, the site is a “super-summer music website inspired by a ‘90s OS,” filled with Vitamin D-laden tunes and accompanying VHS visuals. It’s great.

Not to be outdone, Input has a fun feature on the wild world of Winamp skins that many of us devoted undue time to curating as the visual wrapper for our favorite ’90s-’00s music player. Apparently, you can still download Winamp! They even released a new version recently. I can’t see these skins without being reminded of stalwarts like Kazaa and BearShare (to say nothing of Napster), and, of course, the questionably legal but highly useful app called MyTunes, which allowed a user to see and download the iTunes libraries of everyone with whom they shared a wifi network (for instance, everyone at your college). There was no better way to discover Romanian indie rock.

It doesn’t stop here. For instance, Product Hunt recently featured a product called Banger.Digital: described by its creators, tragically, as “Zoom meets Club Penguin - but with drinking games!” The “parties” take place in an 8-Bit mansion. I tried attending one this week and wound up dispatching my virtual avatar to shoot hoops outside by himself, which pretty much sums it up.

The same spirit that animates these products is inspiring output ranging from love letters to cassette tapes (The Alternative’s Jordan Walsh) to new Facebook initiatives (‘90s collage site E.gg, which first charmed and then ran afoul of copyright and fair use issues). While it’s easy to dismiss these projects as hipster curiosities, I do think there’s a deeper motivation at play: a bias towards reduced choice in the face of infinite content, to cartoon and game visuals, and to remix/pastiche—which exists in one form or another in nearly all breakaway consumer internet products—in the face of a real world that can seem increasingly grim.

Speaking of infinite content…

I enjoyed this piece by Keith Jopling, written for Muse by Clio, in which he describes the paralysis he faces when choosing what music to sample. Jopling’s “listening anxiety” is set against the backdrop of Spotify’s gargantuan catalogue, which is reportedly growing at 40,000 tracks per day. As someone who currently has a “New to Listen” playlist that contains roughly 1,700 songs and yet still finds himself listening to The Chronic multiple times per week, I can empathize. It’s precisely this feeling that drives the trend towards products that artificially constrain choice (see Netflix’s new “shuffle” experiment) or create serendipity and spontaneity through a seemingly magical algorithm (TikTok, for one).

Jesus Toks (?)

I’m just going to leave this here with you.

For your ears only

NPR’s All Things Considered recently published a great story about Agustin Gurza, the editor for the Frontera Collection at UCLA. In addition to Gurza’s ethnomusicological and anthropological work, he catalogues the stickers on the records he collects, seeing them as a window into where these artifacts were bought and sold.

The story includes some wonderful Mexican folk music from the 1930s, including a song called “La Zenaida” by a group called Los Madrugadores (the “early risers”). I’d never heard this one before, but it’s a great corrido/ranchera, complete with perfect vocal harmonies. I would be remiss if I didn’t give a shout out to East LA’s Whittier Boulevard (@Reader BV), which Gurza references, and where I will hopefully find myself (wildfires notwithstanding) in the coming weeks. Enjoy.

See you all next week.

N