Welcome to Edition #48, and the End of March, for whatever that’s worth.

“I can’t wait to forget everything I learned about myself during quarantine.”

NYT NFT

The NYT’s Kevin Roose wrote a crypto-zeitgeist(y) column titled “Buy This NFT Column on the Blockchain!,” thus validating the fact that NFTs and crypto culture (at least at a surface level) are officially having their moment in the sun. A notable number of resolutely analog, non-Trillium reading friends and family—if such descriptors are appropriate for people who don’t read Trillium—sent this piece to me. I leave you to come to your own conclusions as to what this means for good old-fashioned financial speculation in this arena.

The conceit behind Roose’s column was—spoiler alert—that the column itself was for sale as an NFT. The winning bid was an eye-watering 350 ETH ($556,402); the proceeds have gone to charity. Beyond ownership of this world-altering historical artifact, the owner will receive certain perks, including being named in Roose’s follow-up piece and a short voice note from Michael Barbaro (host of The Daily). [Ed.: No points for guessing how many delightfully inquisitive noises he will make in the span of this recording.] Roose also explicitly mentions a key detail that is often overlooked: the NFT of the column does not confer copyright ownership, nor reproduction or syndication rights.

I appreciate the overall tone of the piece, and recommend reading it. Roose is “cautiously optimistic” about the underlying technology, recognizes the potential to improve the earning potential of digital creators, and appropriately calls out rising cases of “shallow hype,” “scammers,” and “get-rich quick hustlers.” All of these things can, indeed, be true at once when there is a market mania such as this one, where a new commercial paradigm rapidly gains attention across a broad swathe of creators and consumers.

NFTs are interesting, yes, for how they create digital scarcity, and for how they enable verification of authenticity, provenance, and transaction history. What I hope to see in the next phase of this movement would be both a proliferation of creator experiments that center on NFTs as a new model for direct fan-to-creator payments and relationships, and an increased focus on the intersection of IP rights and NFTs-as-containers.

For a slightly more “Bostonian” take on this trend (read: scathingly cynical), I recommend perusing the Twitter thread below. [Ed.: I have no idea if the author is from Boston, physically, but I have complete conviction with regard to his spiritual homeland.]

Life’s a Game

TechCrunch’s Lucas Matney wrote this good, short piece on “The Roblox final fantasy,” in which he explained how the company presents a more multi-faceted profile than more traditional peers like Take-Two or Electronic Arts. Roblox, Matney writes, has substantiated its ~$38bn market cap, post IPO, by establishing an “interconnected creative marketplace where gamers can evolve alongside an evolving library of experiences that all share the same DNA (and in-game currency.)” Per the FT, Roblox earned nearly $1.2bn in the first 9 months of 2020 from selling virtual currency to users.

This is, indeed, why I’ve been excited about Roblox, even as someone who’s only spent a couple of hours playing with the game itself. The game-as-platform paradigm is compelling, as is the existence of its own internal economy. It’s trendy to call things “metaverses,” right now, and Roblox would seem to lack some of the more characteristic elements of the accepted definitions thereof: true interoperability to other such “worlds,” for instance. But, it is certainly a meaningfully richer (pun pseudo-intended) experience than traditional video games. Thus far, the market agrees.

One of the things that became established in The Pandemic Era as a trendy in-game behavior is hosting virtual concerts, as discussed extensively in earlier (now-NFT’d) editions of Trillium. From Travis Scott in Fortnite to Lil Nas X in Roblox, as Trillium favorite Cherie Hu writes, numerous artists experimented with this type of digital activation over the past year. (DJ Mag) Interestingly, the financial and power dynamics of these performances are structurally different from those of IRL tours and concerts. Specifically, “traditional concert promoters” like Live Nation are finding themselves without a seat at the table, as artists, labels, and game developers (like Roblox) interact directly.

In some of the same ways that it becomes easy to envision a Future Internet where music labels are no longer relevant to artists’ livelihoods—or must adapt significantly in form and function—it is worth imagining how the roles of concert promoters will change in a world where at least some portion of the events that consumers attend take place online and in walled gardens like games or social media apps. Distribution and monetization of recorded music has already changed fundamentally over the past decades, and most recently with streaming platforms and direct-to-fan monetization models. Now, live event models seem to be undergoing a parallel transition.

Hu proposes that “game developers should give promoters more accessible, flexible development tools to create their own virtual worlds and venues in the metaverse”—(Ed.: there’s that word again!)—and acknowledges a cottage industry that is dedicated to teaching entertainment industry folks how to navigate this new world. I think this is an interesting idea, but personally prefer a paradigm in which those tools are offered directly to individual artists/creators, such that they can independently utilize these creative canvases in the manner that they see fit, without needing the support of yet another 3rd party.

On a related note, Facebook is working towards “realistic digital avatars,” so that we can all attend virtual concerts together but, tragically, without the salutary impacts of digital air-brushing from which we might otherwise benefit. (The Verge) Apparently, Facebook is hard at work on “eye tracking” and “face tracking” for future versions of its Oculus VR devices, with the goal of enabling more life-like VR experiences. [Ed.: I’d prefer less life-like, but perhaps that’s just me.]

Creator Capital

One of the themes of Trillium in recent week has been that creators are finding new ways to capitalize (👏👏👏) on their brand recognition and extensive digital reach. This has taken the form of branded fast food concepts, startup founding, “merch 2.0” production, and now investing. In the past couple of weeks, MrBeast (a well-known YouTuber with 55M+ subscribers on the platform and a host of fledgling business ventures) has been in the news for a number of undertakings. This story is interesting as an exemplar of the trend towards creators-as-holding-companies, wherein the “talent” diversifies their income mix by leveraging online fame into a series of commercial constructs.

Recently, TechCrunch’s Connie Loizos wrote a story about Night Media, MrBeast’s management company, and their launch of a “venture studio to incubate companies that its stars can help shape and grow.” Years after Kim Kardashian, Jessica Alba, Gwyneth Paltrow, and other celebrities perfected the “celeb-branded startup” model with ShoeDazzle, The Honest Company, and Goop, younger creators—who got famous online—are similarly leveraging their influence. Night Media is formalizing this behavior, and, through venture investing, can capture more of the financial upside created (too easy!) by its roster.

In addition, MrBeast announced that he and others are launching a $2M “investment fund that will offer creators up to $250,000 in exchange for a stake in their channels.” (The Verge) The fund, known as Creative Juice, will invest capital and time to help creators grow their channels: an area in which MrBeast’s advisory expertise and personal influence could be meaningful.

It’s great to see creators investing in other creators, as opposed to professional investors capturing their economic gains. But, I have a lot of reservations about equity investing in creators. As I ping-ranted to Hollywood-bound Reader AL: this is one of the messiest equity investments I could imagine. It’s hard to value a creator and their future work, both for investors and for creators themselves. It’s notoriously difficult to equity invest in “services” or “human-driven” businesses, for a variety of reasons, including significant Key Person risk. Revenue dynamics are episodic, which makes them hard to model and to rely upon. And, of course, creators are likely to need equity financing at the moment when they have the least leverage: early in careers, when it’s easy to write a bad deal and hamper future earning potential.

And, like any business helmed by a dominant personality, investors run the risk of a situation like what befell David Dobrik’s Dispo recently. (NYT, h/t Taylor Lorenz again!) After a Cinderella run of positive coverage and valuation (and user) growth, Dispo has become embroiled in scandals pertaining to alleged sexual assault and harassment on the behalf of Dobrik and his “Vlog Squad.” Advertising sponsors like SeatGeek and Dollar Shave Club are pulling out. App store ratings are tanking. Venture capital firm, Spark Capital, which led Dispo’s recent Series A, decided to “sever all ties with the company.” This type of situation certainly isn’t unique to creators, but it is one tangible, recent example of the practical realities of investments in this type of individual and venture.

Stream On

Tim Ingham (Music Business Worldwide) wrote a thoughtful piece in which he calculated that the average revenue per user, for streaming subscriptions, “fell by around 8% globally for the record industry last year.” Ingham’s math is based on the IFPI’s recent Global Music Report, which indicated that global recorded music revenues were up 7.4% YoY to $21.6bn annually.

While six years of consecutive growth is impressive for a business once thought to be on its last legs, Ingham drills deeper into the numbers below the headlines. Specifically, he notes that, while the global record business added 102M subscribers YoY, many of these subscribers seem to have been added in emerging markets with lower average revenues per user. Per Ingham, in 2020, the music industry “was receiving approximately $22.44 per audio streaming subscriber worldwide”; this number was $24.60 in 2019. Hence: a drop of ~8% year over year.

This isn’t necessarily cause for alarm, if you happen to be in the music business. Many tech companies that started in the so-called “First Billion User” countries saw similar downward pressure on their average revenue per user as they pushed into new geographies where users have less purchasing power. It does suggest that, between expansion to emerging markets and aggressive discounting, bundling, and other fast-growth tactics, this trend is likely to continue for Spotify, Apple Music, and others. With all of these new users, many things become possible, including upsell and cross-sell, particularly as economies in their home countries develop. But, this is another interesting nuance to consider when evaluating the blended economics for streaming platforms.

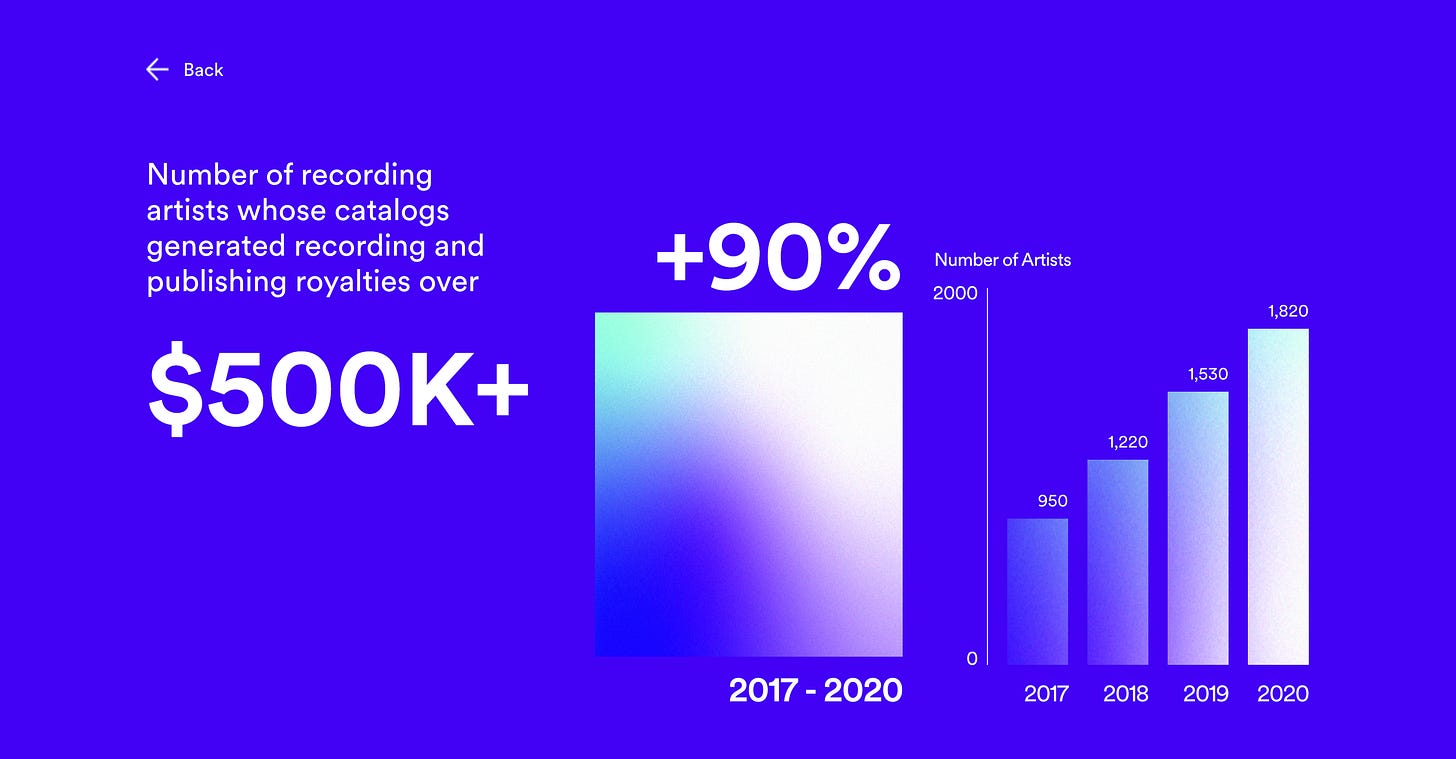

On this note (👏), it’s worth a look at Spotify’s new website: Loud and Clear. Positioned as an attempt towards transparency, motivated by constant artist campaigning for better payouts from the company, Loud and Clear provides a significant amount of data on the $23bn in royalties that Spotify has paid out over its lifetime. Many of the underlying trends look great, with “up and to the right” type trajectories as the platform’s consumer-base has grown.

Of course, averages can be misleading, and the devil is in the details. Much of that $23bn has been paid out to “rights holders,” with middlemen taking cuts at every link of the chain back to the artist who originated the work. 8M creators now have work available on Spotify, with 1.2M receiving over 1,000 listeners per month. As Ingham notes: you may only have a 0.2% chance at making $50k+ per year on Spotify, but that’s actually not that bad relative to your chances of, say, being a professional athlete. I guess that’s comforting?

Writer Reckonings

A couple of weeks ago, Substack (yes, this Substack) put out a blogpost designed to provide context on the Substack Pro(gram), which pays out upfront sums to certain established writers in exchange for their publishing on the platform. For their first year on Substack, “Pro” writers agree “to let Substack keep 85% of the subscription revenue.” You can see the appeal to Substack—top-flight writers bringing audience attention to the platform and generating meaningful fees—and to the writers themselves: risk mitigation when leaving more established salaried media jobs.

There has been a backlash against the company in the Twitter echo-chamber and in various thinkpieces that I have generally ignored in an attempt to preserve my rapidly vanishing equanimity. Critics are displeased with Substack’s lack of transparency around to whom they pay advances, and with the company’s perceived support of unabashedly conservative voices (e.g., Glenn Greenwald). While Substack itself is intended as an unbiased, objective platform for writers (of all types) who can then exercise their independence as they see fit, it is a fair counterpoint that choosing to whom advance funds are allocated does influence the publications on the site. And, as Casey Newton notes in a thoughtful Platformer snippet (on Substack): some readers are concerned that their subscription fees are being used to fund advances to writers whose views they find unsettling.

Part of this is a question of your mental model around Substack. Is it a place that you go to browse and discover writing because you trust their curation? Or do you simply discover individual Substacks elsewhere—say, Twitter—and subscribe to those writers whom you find compelling? Do you read Substacks on Substack (or in Reader), or do you receive them in your inbox? Is Substack to be a “faceless publisher,” in Ben Thompson’s words, or do you believe that they are making editorial decisions for which they should be held accountable? Speaking of Thompson, I generally agree with his recent post on “The Sovereign Writer,” in which he articulates a theory of Substack as an infrastructural enabler of direct relationships between writer and reader—where the reader has exercised choice!—rather than as a curatorial presence.

My solution to all of this is to let all the human writers go on vacation and simply let GPT-3 go to work. One day, when AI Trillium is established comfortably on its algorithmic throne and I am equivalently established in more luxurious climes, with the rustling of palm trees in my ears, this might all seem less existentially threatening.

For your ears only

My “aural xanax” playlist seems to be growing these days. Probably not worth reading into that too much. This week, I’ve been spending a lot of time with Mary Lattimore’s 2020 album, Silver Ladders. Lattimore is a supremely talented harpist, based in Los Angeles. This album was produced by Slowdive’s Neil Halstead and it is excellent.

You probably have a pretty fixed notion of what “harp music” sounds like. I know I did! This album will change that. Lattimore and Halstead mix in electronic textures, synth sounds, guitar bits, and other atmospherics that complement the original compositions. At times, you can imagine some of the prettier instrumental bits from albums like Radiohead’s Kid A. Recommended for focused listening, background companionship, and all other manners of engagement.

See you all next week.

N